Abstract

Background

The integration of sex and gender aspects into the research process has been recognized as crucial to the generation of valid data. During the coronavirus pandemic, a great deal of research addressed the mental state of hospital staff, as they constituted a population at risk for infection and distress. However, it is still unknown how the gender dimension was included. We aimed to appraise and measure qualitatively the extent of gender sensitivity.

Methods

In this scoping review, we searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL PsycINFO and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) from database inception to November 11, 2021. All quantitative studies with primary data published in English, German, or Spanish and based in the European Union were selected. Included studies had to have assessed the mental health of hospital staff using validated psychometric scales for depression, anxiety, PTSD symptoms, distress, suicidal behavior, insomnia, substance abuse or aggressive behavior. Two independent reviewers applied eligibility criteria to each title/abstract reviewed, to the full text of the article, and performed the data extraction. A gender sensitivity assessment tool was developed and validated, consisting of 18 items followed by a final qualitative assessment. Two independent reviewers assessed the gender dimension of each included article.

Results

Three thousand one hundred twelve studies were identified, of which 72 were included in the analysis. The most common design was cross-sectional (75.0%) and most of them were conducted in Italy (31.9%). Among the results, only one study assessed suicidal behaviors and none substance abuse disorders or aggressive behaviors. Sex and gender were used erroneously in 83.3% of the studies, and only one study described how the gender of the participants was determined. Most articles (71.8%) did not include sex/gender in the literature review and did not discuss sex/gender-related findings with a gender theoretical background (86.1%). In the analysis, 37.5% provided sex/gender disaggregated data, but only 3 studies performed advanced modeling statistics, such as interaction analysis. In the overall assessment, 3 papers were rated as good in terms of gender sensitivity, and the rest as fair (16.7%) and poor (79.2%). Three papers were identified in which gender stereotypes were present in explaining the results. None of the papers analyzed the results of non-binary individuals.

Conclusions

Studies on the mental health of hospital staff during the pandemic did not adequately integrate the gender dimension, despite the institutional commitment of the European Union and the gendered effect of the pandemic. In the development of future mental health interventions for this population, the use and generalizability of current evidence should be done cautiously.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is rising awareness of the need to integrate sex and gender in health research to increase the validity and generalizability of study findings. Gender is a multidimensional variable describing identity, social norms, and relations between individuals, while sex is a biological construct encompassing the biological characteristics enabling reproduction [1, 2]. Although traditionally conceptualized as two separate constructs, sex and gender are interrelated, and the binary distinction between women/men and female/male does not capture all the existing variability. In accordance with other authors, we used the shortened version sex/gender. This highlights that even being distinct concepts, there are potential interrelations between biological and sociocultural aspects of being a man, a woman, or a sex/gender diverse person [3]. Both sex and gender can influence the presentation of diseases, the diagnosis, and even the access to treatment and available support [2, 4,5,6,7]. In the case of mental health disorders, there are clear epidemiological differences regarding sex/gender, although it remains unclear to what extent the differences are due to biological or social factors. In general, externalizing disorders, such as violent behavior or substance abuse, are more often reported among men, while the majority of patients with internalizing syndromes like depression and anxiety are women [8]. This pattern was also observed during the COVID-19 pandemic: most studies revealed that women presented more depressive and anxiety symptoms than men, and this was particularly true in the healthcare sector [9,10,11,12,13]. Front-line medical staff had the highest levels of distress and perception of life threat, as hospitals were one of the main settings for infection during the first waves.

Gender equity has been acknowledged as a relevant transversal issue in European Union (EU) policymaking since the late 1990ies, when the concept of gender mainstreaming was introduced [14]. Sex/gender sensitivity can be conceptualized as the consideration of sex/gender aspects in all the steps of the research process [15]. Additionally, it strives to provide equal participation of women and men in scientific work and consider non-binary individuals [16]. Even if the primary research question of a health study does not focus on sex or gender, sensitivity towards it is warranted because all cells are sexed, and all bodies are gendered [17, 18]. In the last decades, several countries and institutions developed guidelines and recommendations on how to achieve sex/gender sensitivity, but the implementation has been slow [19,20,21]. The EU, in particular, published a guideline in 2012 on how to include gender sensitivity in research [22], but also high-impact journals showed their commitment to the appropriate use of sex/gender and provision with disaggregated data [23]. Additionally, the SAGER guidelines provide orientation for journal editors on how to evaluate the inclusion of gender in a paper. Parallelly, individual studies provided examples of good practices respecting gender or checked the current status of the integration of sex and gender in research proposals [3, 24,25,26]. However, o date, there is no tool to adequately assess the gender sensitivity of an article.

A lack of sex/gender sensitivity can lead to biased research results, delayed diagnosis or undertreatment [27, 28]. In terms of studies on the psychological impact of the pandemic on healthcare workers, evidence as to how sex/gender has been integrated into research is almost nonexistent. Although an emerging body of literature demonstrated the gendered impact of the pandemic on this population [11, 29, 30], to date, no study has assessed how sex and gender have been included globally throughout the research process. In this context, we set out to assess the extent of gender sensitivity in studies on the psychological impact of hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the strong EU commitment to sex/gender sensitivity in research, we focused specifically on EU studies and assessed how and to what extent studies included these variables.

Review question and objectives

Is current literature about the psychological impact of the coronavirus on healthcare workers gender-sensitive? Specifically to:

-

How sex/gender is assessed in the articles.

-

How are the results and conclusions presented with respect of sex/gender.

-

Potential gender bias in the interpretation of results.

Materials and methods

We conducted a scoping review of peer-reviewed literature in line with the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. The respective protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XBU5A. We chose a scoping review methodology because our objective was not to answer a specific research question but to do a comprehensive mapping of the published studies.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched (from database inception to 11 November 2021) MEDLINE via OvidSP, EMBASE via OvidSP, CINAHL via EBSCO, PsycINFO via OvidSP, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) via web of Science. The search terms were developed iteratively by the research team including a professional librarian and included three sets of key terms (Healthcare workers, Mental health, and Hospital) combined with Boolean logic to search for relevant papers. The complete search strategy for each database is provided in the supplemental material.

Study selection

To meet the inclusion criteria, articles had to: 1) be peer-reviewed and use quantitative methods; 2) use validated psychometric tests of depression, anxiety, distress/stress, substance use/abuse, suicidal ideation, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or quality of life; 3) focus on hospital-based healthcare workers; 4) be conducted in the European Union. We excluded non-peer-reviewed publications, populations apart from hospital healthcare workers, studies that did not address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, non-European studies, and studies published in another language than English, Spanish, or German. The identified studies were stored, deduplicated, and later imported into the software Rayyan for screening by two independent reviewers of titles, abstracts, and full-text articles against the eligibility criteria. We resolved any disagreement by consensus.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted from included studies using a pilot extraction form in the Google Forms platform form. It included study characteristics (e.g., design, sample, location), sex/gender of first and last author, outcome, results, and the items in the assessment tool. Data extraction for each included article was performed independently by two reviewers (MLA as first reviewer, NZ, AU and ML as second reviewer).

We first performed a bibliography search to find any instrument to appraise the sex/gender sensitivity of a study. As we did not find any validated appraisal tool suitable for our study, we selected critical items from available instruments [15, 22, 31,32,33,34,35,36]. We primarily followed the structure of the SAGER guidelines, designed to guide the report of sex/gender in research, and developed the appraisal tool questions based on this structure. The items of the tool were further developed and revised by two senior researchers with expertise in gender studies (TB and MS) and a PhD student in gender studies (MLA). Each item was redefined until consensus was reached. We developed 18 items divided into five sections, followed by a rating of each section and the overall rating using an ordinal scale with the items "excellent", "good", "fair" and "poor”. Subsequently, we tested the inter-rater reliability. Initially, we conducted a pilot test with 10 randomly selected items and redefined the items with the lowest inter-rater agreement values. In the second step, we scored 18 articles that mentioned sex and/or gender in the title or abstract. A researcher with expertise in gender studies (MLA) and a second rater (EF) participated in this process. Most of the values were in an acceptable range. The kappa for the item "overall rating" was 0.577, showing moderate agreement among the raters. Supplementary Appendix provides the appraisal tools and the κ scores for inter-rater agreement.

Results

We identified 3112 articles after the removal of duplicates (Fig. 1). We assessed the full texts of 235 articles for eligibility. Of these, 125 studies did not examine the population under study (other populations than healthcare workers or healthcare workers from outside the EU); 17 articles did not contain original data; 12 did not examine the required outcomes; 4 were not in English, German, or Spanish, 3 did not have a quantitative study design and 3 were background articles. We included 72 independent studies in the analysis [30, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107] (Fig. 1). The complete list and characteristics of the included studies is provided in Table 1.

Study characteristics and outcomes

The most common design was an observational cross-sectional study (54 studies; 75.0%), followed by prospective cohort studies (8 studies, [11.1%]). Most studies were conducted in Italy (31.9%), Spain (18.1%) and France (8.3%), while the remainder came from 11 other EU countries (Fig. 2). The number of participants ranged between 3 and 5440, and the percentage of women was between 34 and 100%. The most frequent outcome variable was depression (49 studies [68.1%]) and anxiety (44 studies [61.1%]). Only one study reported suicidal behavior (1.4%) in the outcome variables, and none evaluated violent or risky behaviors or substance abuse. However, five articles included alcohol or substance use as a sociodemographic variable [44, 51, 81, 84, 108] and one checked for the presence of substance abuse disorders before the pandemic [105]. Overall, the most used psychometric tests were the Impact of Event scale (n = 18), the Patient Health Questionnaire (n = 15), and the Maslach Burnout Inventory (n = 14). Regarding sociodemographic variables that potentially intersect with sex/gender, age, occupation and marital status were present in almost all articles but did not refer to the variables as gender-relevant or used then in a intersectional analysis. However, other variables such as religion [73], migration background [77, 107], and ethnicity [54] were rarely mentioned. In terms of authorship, women constituted 52.8% of the first authors and 41.7% of the last authors. A description of the included studies is provided in the appendix Table 1.

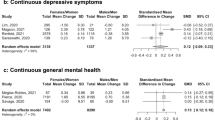

Most of the studies that provided disaggregated data reported gender differences in depressive [30, 41, 48, 64, 75, 92, 109], anxiety [41, 48, 58, 64, 70, 71, 75, 82, 99, 109], stress [30, 38, 52, 59, 64, 96, 109], post-traumatic stress [41, 48, 75, 82, 109] and insomnia [59] symptoms. In general, symptoms were worse among women/females, except two that revealed more depressive symptoms in males/men [69, 88], one of which was rated as fair in terms of gender sensitivity [88]. Regression analyses showed that being a woman was a risk factor for the presentation of stress [30, 39, 41, 42, 52, 64, 76, 102], anxiety [40, 41, 47, 48, 67, 71, 72, 81, 82, 86, 102], depression [30, 41, 47, 48, 52, 67, 72, 74, 81, 92, 102] PTSD [48, 67, 72, 102] and insomnia [71]. Among the three articles rated as good in gender sensitivity, two found statistically significant gender differences in mental health variables, being woman more affected than men [74, 30], and one did not [97]. Advanced modelling techniques were identified in three of the articles. In one of them, age was found to interact with gender: as age increased, symptoms of depression and anxiety decreased in men, whereas they remained stable in women [64]. A second study concluded that stress symptoms, resilience, emotional symptoms, and self-efficacy mediated the influence of the gender variable on psychiatric symptoms [74]. Finally, the third study found that the presence of previous psychiatric history had a greater impact on depressive symptoms in men [30]. Two of this three articles were rated as good in terms of gender sensitivity [74, 30] and one as fair [64].

Sex/gender sensitivity

A sex/gender sensitivity assessment was performed in each study (Table 2). Seventy-one publications mentioned sex or gender, but only one defined it [30]. A total of 60 articles (83.3%) used the terms sex or gender erroneously or interchangeably. For example, gender was divided into two categories (male and female) that correspond to the sex of individuals, or all terms (sex, gender, male/female, women/men) were used interchangeably throughout the article. None of the papers specifically mentioned the non-binary population. However, five (6.9%) provided the additional label of "other" or "diverse" [46, 54, 66, 105, 107] in the data collection of the sex/gender. In the introduction, most studies did not refer to sex/gender differences or similarities in the literature review (51 studies [71.8%]), and only five (7.0%) mentioned sex/gender in the objectives of the study. In the methods section, one article (1.4%) explained how gender was determined. One paper provided different cut-off values for women in one of the psychometric scales [47], while all the others used the same cut-off values without providing literature to justify it.

In the analysis and reporting of the results, 27 studies (37.5%) disaggregated outcome data in relation to sex/gender studies [30, 38, 41, 48, 53, 58, 59, 64, 68,69,70,71, 74, 75, 77, 82, 83, 88, 92, 95,96,97,98,99, 102, 104, 105]. Fourteen studies (19.7%) had an adequate representation of women/females or men/males (measured as a proportion between 40 to 60% or equivalent to the sex/gender ratio in the underlying population) [30, 43, 50, 54, 57, 60, 66, 74, 75, 83, 84, 94, 100, 107]. In contrast, 57 studies had an overrepresentation of one gender, and one study included only women [101]. 47 studies included sex/gender as a factor in the regression analysis, but very few (3 studies [4.2%]) conducted advanced modeling techniques with the sex/gender variable. Ten studies (13.9%) referred to sex/gender-related research or theories when interpreting their findings. Among the topics addressed were gender roles [95] caretaking labors [41, 95, 97] work-family conflicts [53, 76, 103, 110] and gender stereotypes of masculinity and femininity [74, 110]. One article highlighted the importance of introducing a gender perspective for the mental health of both men and women [87], even without clearly including a gender theoretical framework in the discussion.

Of note, we identified gender stereotypes in three studies (4.2%). Beneria et al. [39] explain that “women had more symptoms of stress, probably related to the […] frustration with the death of patients whom they care”. The second example is that of Simonetti et al. [71] when they state that “higher levels of anxiety in female nurses are due to worries about infecting their children” and continue with “Higher self-efficacy in males probably [due to] their ability to solve problems and find solutions". In the third identified study [92], they note that “women [are] biologically more disposed to develop higher levels of anxiety and PTSD than men”, with no reference to social aspects. Finally, regarding the overall assessment of gender sensitivity, we rated only three papers (4.2%) as good [30, 74, 97]. N = 12 articles were rated as fair (16,7%), and the remaining as poor (n = 57 studies, [79,2%]). We did not identify any papers with excellent gender sensitivity (Fig. 3). There weren’t statistical differences in the proportion of women in the first or second author respecting gender sensitivity (p > 0,05).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to comprehensively assess the gender sensitivity of COVID-19 research on the mental health of hospital staff. Our results suggest that, in general, gender sensitivity is low. Of the 72 studies included in the analysis, only three were rated as good in terms of gender sensitivity. Most of the studies suffered from important methodological flaws, such as using sex and gender erroneously or interchangeably, not specifying how the sex/gender of participants was determined, and lacking sex-disaggregated data. In most cases, non-binary individuals were not considered, nor were other variables such as migrant background or sexual orientation, which help identify marginalized identities within and between genders. In the discussion, very few articles used theoretical frameworks to situate their findings in relation to the gendered psychological impact of the pandemic and, in three articles, the results were explained based on gender stereotypes.

In our review, we assessed the rigor with which the concepts of sex and gender are treated. Although the vast majority of the articles reported the variables of sex or gender in their study, the reality is that more than 80% misused these concepts. This confusion is a widespread phenomenon that occurs even in gender-specific medical journals, where one would expect greater precision [111, 112]. For this reason, various institutions, including the EU, have been committed to promoting the correct distinction between the two [22, 23, 36, 113]. Another important finding is the lack of non-binary options for reporting the sex or gender variable. Only one study offered the option of "diverse" [107] and three “Other/prefer not to say” [46, 54, 66], terms that not clearly reflect the existing variability [114]. One claimed to have eliminated from the analysis individuals who did not identify as either man or woman [105] without specifying how these individuals were identified. In general, non-binary individuals are known to suffer higher rates of suicide, depression, and anxiety disorders [114] and in the case of healthcare workers, they are victims of discrimination and unable to disclose their identity [115, 116]. The fact that both the identification and analysis of trans or non-binary individuals has been neglected reflects the need for greater visibility of this population.

We only identified 14 studies with adequate sex/gender proportions [30, 43, 50, 54, 57, 60, 66, 74, 75, 83, 84, 94, 100, 107]. Like other authors [117], we considered that an article had an adequate proportion of men and women in two cases: in the case of proportions between 40 and 60%, or if the authors justified the reason for the sample having unequal values. During the pandemic more than 70% of health care workers were women [118], so it is possible that in many studies the proportions corresponded to those of the study population. However, the investigators should have clarified the reasons why the proportions were not equal in their sample, for example, by referring to the study population. As other authors have argued, the selection of subjects should seek the best number to facilitate the validity and representativeness of the results, even at the cost of unequal gender proportions [119], and this was not the case in almost 80% of the included studies. Methodological decisions on sex and gender in relation to the study population should be reported and justified [33, 120], as failure to do so may lead to unrepresentative results. For example, in clinical trials of acute coronary syndrome, the overrepresentation of men/males led to extrapolation of incorrect conclusions in women [121].

The way sex and gender were reported and included in the methodology was also assessed. Sex/gender disaggregated data is one-way researchers can discover differences in outcome measurements. In addition, it is one of the steps recognized by the EU Commission for the development of gender statistics. We found that only 37.5% of the included studies disaggregate data by sex or gender [30, 38, 41, 48, 53, 58, 59, 64, 68,69,70,71, 75, 74, 77, 82, 83, 88, 92, 95,96,97,98,99, 102, 104, 105]. This percentage is, however, higher than in clinical trials registered in COVID-19, where only 17.8% of the registered studies disaggregated the data [122] as well as in clinical trials published in high-impact journals, where the proportion drops to 14.0% [117]. In a study on authorship and sex disaggregation of data in COVID-19 research published in Spanish journals, the proportion was as low as 1% [123]. The reasons for these differences remain unknown. It is important for future research to determine whether EU policies had a positive influence on mental health research conducted during the pandemic. We then assessed what percentage of articles performed advanced statistical analysis with the variable of sex or gender. The underlying theory is that controlling for sex or gender treats these variables as confounders, rather than variables of importance to the research question. Ostensibly, it allows sex or gender differences in the outcome to be assessed, but it also forces this difference to be the same at all levels of the predictor [124]. This was, in fact, the most common way to include sex/gender in regression analysis. In our opinion, a more advanced approach would be to assess whether sex or gender is moderated or intersects with other variables [125], models that we only identified in three articles. Additionally, three other studies reported ethnicity and migration [107], but none subsequently performed any intersectional analysis.

One of our main findings is the identification of gender stereotypes in peer-reviewed publications. Gender stereotypes are general expectations and overgeneralized beliefs about people's characteristics based solely on their sex [126, 127]. In one of the studies, for example, the authors claim that women were more stressed by worrying about deceased patients, without evidence to substantiate this claim [39]. The perpetuation of the stereotype of masculinity as cold and emotionless precludes further development of programs for the male population. Indeed, they too were undoubtedly affected by patient deaths during the pandemic, but were less likely to seek support given the traditional male norm of being strong, in control, and able to avoid emotions [128]. In another example the authors state that the higher levels of anxiety found in female nurses were due to concern about infecting their children [71]. They go on to report that men had higher self-efficacy scores due to their ability to solve problems and find solutions. This statement reflects the primary importance we place on task performance when judging men and on social relationships when considering women [127]. Moreover, they also reinforce the gendered expectation that children are women's (and not men's) priority. In the last example, the authors attribute higher anxiety and PTSD in female health care workers to inherent biological factors [92] However, the authors do not mention the social factors that influence the poorer mental health of women in the healthcare sector. For example, problems in reconciling work and family life have been related to higher depression symptoms in women doctors [129]. In addition, they are victims of significant levels of workplace harassment and violence [130, 131], which predisposes them to a higher risk of developing PTSD symptoms when exposed to new traumatic experiences, such as the pandemic.

In our review most studies focused on internalizing disorders. Externalizing behaviors, such as drug use, have been little studied, or even undetected, in this population. Given that men are more likely to engage in risky behaviors in stressful situations [132], the impact of the pandemic on male healthcare workers may be underestimated. In addition, the fact that research focuses primarily on internalizing disorders may mask a stereotypical idea of femininity illness in women-dominated field such as medicine. Women also engage in substance abuse behavior, but it is stigmatized behavior and tends to be hidden [133]. In addition, men are less likely to seek psychiatric care and disclose mental health symptoms [134, 135], but the influence of masculinity on symptom reporting was only superficially mentioned in one article [74]. Present research will determine mental health interventions for healthcare workers in future pandemics. If knowledge production is biased, it may produce inaccurate results and the subsequent mental health programs may not be effective.

Our study has, however, some limitations. The inclusion of EU studies facilitates contextualization of the findings but may affect their generalizability. There are more institutions at the international level that also promote the inclusion of the gender dimension. Examples are the Canadian Institute of Health Research [136] or the U.S. National Institute of Health [113]. Other regions, on the contrary, do not have public policies aimed at integrating gender in research. Since there is a wide variation by country, conclusions should be drawn with caution. A second limitation is the focus on hospital staff. It is possible that gender sensitivity in studies of mental health in outpatient staff or in the general population may be different. In addition, tools for assessing the integration of sex/gender in research studies need to be further developed in the future.

Conclusions

Our study shows that most European research on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on hospital staff is insufficiently sensitive to sex/gender, even after a clear public commitment by the EU. Gender biases may be present from study design to interpretation of results, and this may interfere with the development of effective prevention and treatment interventions in future pandemics. The impact on non-binary individuals was neglected and remains unknown, as is the interplay between gender and other variables such as occupation, ethnicity, or sexual orientation since no interaction analyses were performed. Our findings call for a greater inclusion of the sex/gender dimension in future research to develop effective interventions in future pandemics.

Available of data and materials

This work analyzed secondary sources, which are cited in the manuscript. Additional data from the analysis can be requested to the corresponding author.

References

Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting sex, gender, or both in clinical research? JAMA. 2016;316(18):1863–4.

Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, Brinton RD, Carrero JJ, DeMeo DL, et al. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet. 2020;396(10250):565–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31561-0.

Jahn I, Börnhorst C, Günther F, Brand T. Examples of sex/gender sensitivity in epidemiological research: results of an evaluation of original articles published in JECH 2006–2014. Health Res Policy Syst. 2017;15(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0174-z.

McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1027–35. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022395611000458.

Boerma T, Hosseinpoor AR, Verdes E, Chatterji S. A global assessment of the gender gap in self-reported health with survey data from 59 countries. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):675. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3352-y.

Sen G, Östlin P, George A. Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why it exists and how we can change it. WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2007.

Hennein R, Bonumwezi J, Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Tineo P, Lowe SR. Racial and gender discrimination predict mental health outcomes among healthcare workers beyond pandemic-related stressors: findings from a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34501818.

Boyd A, van de Velde S, Vilagut G, de Graaf R, O’Neill S, Florescu S, et al. Gender differences in mental disorders and suicidality in Europe: results from a large cross-sectional population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2015;173:245–54. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165032714006983.

He L, Wang J, Zhang L, Wang F, Dong W and Zhao W. Risk factors for anxiety and depressive symptoms in doctors during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12:687440. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.687440.

Sun D, Yang D, Li Y, Zhou J, Wang W, Wang Q, et al. Psychological impact of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak in health workers in China. Epidemiol Infect. 2020.

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976–e203976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976.

Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, di Lorenzo G, di Marco A, Siracusano A, et al. Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e2010185–e2010185. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10185.

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Wang H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. Elsevier Ireland Ltd; 2020;291:113190.

Gender mainstreaming at the Council of Europe - Gender Equality - www.coe.int. Available from: https://www.coe.int/en/web/genderequality/gender-mainstreaming.

Trbovc JM, Hofman A. IMP Toolkit for Integrating Gender- Sensitive Approach into Research and Teaching. Garcia Working Papers. 2015;6:50. Available from: www.garciaproject.eu.

European Commission: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Gender in EU-funded research – Toolkit, Publications Office. 2014. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/74150.

Krieger N. Genders, sexes, and health: what are the connections—and why does it matter? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(4):652–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg156.

of Medicine I. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Wizemann TM, Pardue ML, editors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. Available from: https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/10028/exploring-the-biological-contributions-to-human-health-does-sex-matter.

Verloo M. Gender mainstreaming: Practice and prospects. Report prepared for the Council of Europe. EG. 1999a;(99):13.

World Health Organization W. Gender Mainstreaming in Health. 2001;(January):6–8. Available from: http://apps.searo.who.int/PDS_DOCS/B3708.pdf.

Mazure CM, Jones DP. Twenty years and still counting: including women as participants and studying sex and gender in biomedical research. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15(1):94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0251-9.

Commission E, Innovation DG for R and. Gender in EU-funded research : toolkit. Publications Office; 2014.

Raising the bar for sex and gender reporting in research. Nat Metab. 2022;4(5):495. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42255-022-00581-1.

Alcalde-Rubio L, Hernández-Aguado I, Parker LA, Bueno-Vergara E, Chilet-Rosell E. Gender disparities in clinical practice: are there any solutions? Scoping review of interventions to overcome or reduce gender bias in clinical practice. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01283-4.

Palmer-Ross A, Ovseiko PV, Heidari S. Inadequate reporting of COVID-19 clinical studies: a renewed rationale for the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(4):10–3.

van Hagen LJ, Muntinga M, Appelman Y, Verdonk P. Sex- and gender-sensitive public health research: an analysis of research proposals in a research institute in the Netherlands. Women Health. 2021;61(1):109–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2020.1834056.

Lancet T. Cardiology’s problem women. Lancet. 2019;393(10175):959. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30510-0.

Gauci S, Cartledge S, Redfern J, Gallagher R, Huxley R, Lee CMY, et al. Biology, bias, or both? The contribution of sex and gender to the disparity in cardiovascular outcomes between women and men. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2022;24(9):701–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-022-01046-2.

Wenham C, Smith J, Morgan R. COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):846–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30526-2.

López-Atanes M, Pijoán-Zubizarreta JI, González-Briceño JP, Leonés-Gil EM, Recio-Barbero M, González-Pinto A, et al. Gender-Based Analysis of the Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Workers in Spain. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.692215.

Doull M, Runnels V, Tudiver S, Boscoe M. sex and gender in systematic reviews planning tool. The campbell and cochrane equity methods group. 2011;1–2. Available from: http://methods.cochrane.org/sites/methods.cochrane.org.equity/files/public/uploads/SRTool_PlanningVersionSHORTFINAL.pdf.

Morgan T, Williams LA, Gott M. A feminist quality appraisal tool: exposing gender bias and gender inequities in health research. Crit Public Health. 2017;27(2):263–74.

Heidari S, Babor TF, De Castro P, Tort S, Curno M. Sex and Gender Equity in Research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2016.

World Health Organization (WHO). TDR intersectional gender research strategy. 2020.

Ruiz-Cantero MT, Vives-Cases C, Artazcoz L, Delgado A, García Calvente M del M, Miqueo C, et al. A framework to analyse gender bias in epidemiological research. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978). 2007 Dec 1;61(Suppl 2):ii46 LP-ii53. Available from: http://jech.bmj.com/content/61/Suppl_2/ii46.abstract.

Commission E, Innovation DG for R and. Approaches to inclusive gender equality in research and innovation (R&I). Publications Office of the European Union; 2022.

Aguglia A, Amerio A, Costanza A, Parodi N, Copello F, Serafini G, et al. Hopelessness and Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Any Role for Mediating Variables? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34207303.

Ali S, Maguire S, Marks E, Doyle M, Sheehy C. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers at acute hospital settings in the South-East of Ireland: an observational cohort multicentre study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):1–6.

Beneria A, Arnedo M, Contreras S, Pérez-Carrasco M, Garcia-Ruiz I, Rodríguez-Carballeira M, et al. Impact of simulation-based teamwork training on COVID-19 distress in healthcare professionals. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):515. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02427-4.

Bidzan M, Bidzan-Bluma I, Szulman-Wardal A, Stueck M, Bidzan M. Does Self-Efficacy and Emotional Control Protect Hospital Staff From COVID-19 Anxiety and PTSD Symptoms? Psychological Functioning of Hospital Staff After the Announcement of COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Front Psychology. 2020;11. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm5&NEWS=N&AN=33424673.

Collantoni E, Saieva AM, Meregalli V, Girotto C, Carretta G, Boemo DG, et al. Psychological distress, fear of covid-19, and resilient coping abilities among healthcare workers in a tertiary first-line hospital during the coronavirus pandemic. J Clin Med. 2021;10(7):1465.

Di Giuseppe M, Nepa G, Prout TA, Albertini F, Marcelli S, Orrù G, et al. Stress, burnout, and resilience among healthcare workers during the covid-19 emergency: the role of defense mechanisms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5258.

Dionisi T, Sestito L, Tarli C, Antonelli M, Tosoni A, D’Addio S, et al. Risk of burnout and stress in physicians working in a COVID team: A longitudinal survey. International Journal of Clinical Practice. Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Catholic University of Rome, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy Internal Medicine Unit, Department of Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Columbus‐Gemelli Hospit; 2021;75. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=153125177&lang=es&site=ehost-live.

Ghio L, Patti S, Piccinini G, Modafferi C, Lusetti E, Mazzella M, et al. Anxiety, Depression and Risk of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Health Workers: The Relationship with Burnout during COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34574851.

Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D’Aniello GE, Stramba Badiale C, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, Stramba Badiale M, Riva G, Castelnuovo G and Molinari E. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: A cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684.

Haravuori H, Junttila K, Haapa T, Tuisku K, Kujala A, Rosenstrom T, et al. Personnel Well-Being in the Helsinki University Hospital during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Prospective Cohort Study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med17&NEWS=N&AN=33126583.

Lamiani G, Borghi L, Poli S, Razzini K, Colosio C, Vegni E. Hospital employees’ well-being six months after the covid-19 outbreak: results from a psychological screening program in italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5649.

Lasalvia A, Bonetto C, Porru S, Carta A, Tardivo S, Bovo C, et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e1.

Lucas D, Brient S, Eveillard BM, Gressier A, Le Grand T, Pougnet R, et al. Health impact and psychosocial perceptions among french medical residents during the sars-cov-2 outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8413.

Magnavita N, Soave PM, Antonelli M. A One-Year Prospective Study of Work-Related Mental Health in the Intensivists of a COVID-19 Hub Hospital. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34574811.

Man MA, Toma C, Motoc NS, Necrelescu OL, Bondor CI, Chis AF, et al. Disease Perception and Coping with Emotional Distress During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Survey Among Medical Staff. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med17&NEWS=N&AN=32645962.

Matarazzo T, Bravi F, Valpiani G, Morotti C, Martino F, Bombardi S, Bozzolan M, Longhitano E, Bardasi P, Roberto DV, Carradori T. Coronacrisis—an observational study on the experience of healthcare professionals in a university hospital during a pandemic emergency. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084250.

Pappa S, Athanasiou N, Sakkas N, Patrinos S, Sakka E, Barmparessou Z, et al. From Recession to Depression? Prevalence and Correlates of Depression, Anxiety, Traumatic Stress and Burnout in Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Greece: A Multi-Center, Cross-Sectional Study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=33804505.

Roberts T, Daniels J, Hulme W, Hirst R, Horner D, Lyttle MD, et al. Psychological distress and trauma in doctors providing frontline care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom and Ireland: a prospective longitudinal survey cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e049680. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/7/e049680.abstract.

Secosan I, Virga D, Crainiceanu ZP, Bratu LM, Bratu T. Infodemia: Another Enemy for Romanian Frontline Healthcare Workers to Fight during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2020;56. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=33317190.

Secosan I, Virga D, Crainiceanu ZP, Bratu T. The Mediating role of insomnia and exhaustion in the relationship between secondary traumatic Stress and Mental Health Complaints among Frontline Medical Staff during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav Sci. 2020;10(11):164.

Stocchetti N, Segre G, Zanier ER, Zanetti M, Campi R, Scarpellini F, et al. Burnout in Intensive Care Unit Workers during the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Single Center Cross-Sectional Italian Study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34198849.

Tiete J, Guatteri M, Lachaux A, Matossian A, Hougardy JM, Loas G, et al. Mental health outcomes in healthcare workers in COVID-19 and Non-COVID-19 care units: a cross-sectional survey in Belgium. Front Psychol. 2021;11(January):1–10.

Tselebis A, Lekka D, Sikaras C, Tsomaka E, Tassopoulos A, Ilias I, et al. Insomnia, Perceived Stress, and Family Support among Nursing Staff during the Pandemic Crisis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;8. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm5&NEWS=N&AN=33114662.

Ungureanu BS, Vladut C, Bende F, Sandru V, Tocia C, Turcu-Stiolica RA, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Health-Related Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Training Among Young Gastroenterologists in Romania. Front Psychology. 2020;11. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm5&NEWS=N&AN=33424692.

Van Der Goot WE, Duvivier RJ, Van Yperen NW, De Carvalho-Filho MA, Noot KE, Ikink R, et al. Psychological distress among frontline workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study. PLoS One. 2021;16(8 August):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255510.

Zerbini G, Ebigbo A, Reicherts P, Kunz M, Messman H. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of covid-19 – a survey conducted at the university hospital augsburg. GMS German Med Sci. 2020;18:1–9.

Altmayer V, Weiss N, Cao A, Demeret S, Rohaut B, Le Guennec L, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 crisis in Paris: A differential psychological impact between regular intensive care unit staff members and reinforcement workers. Vol. 34, Australian Critical Care. [Altmayer, Victor; Weiss, Nicolas; Cao, Albert; Demeret, Sophie; Rohaut, Benjamin; Guennec, Loic Le; Rea-Neuro-Pitie-Salpetriere Study] Sorbonne Univ Paris, Paris, France. Le Guennec, L (corresponding author), Sorbonne Univ, La Pitie Salpetriere Hosp,; 2021.

Erquicia J, Valls L, Barja A, Gil S, Miquel J, Leal-Blanquet J, et al. Emotional impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in one of the most important infection outbreaks in Europe. Medicina clinica (English ed.). 2020;155. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm5&NEWS=N&AN=33163628.

Marcomini I, Agus C, Milani L, Sfogliarini R, Bona A, Castagna M. COVID-19 and post-traumatic stress disorder among nurses: a descriptive cross-sectional study in a COVID hospital. La Medicina del lavoro. 2021;112. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=34142675.

Roberts T, Daniels J, Hulme W, Hirst R, Horner D, Lyttle MD, et al. Psychological distress during the acceleration phase of the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of doctors practising in emergency medicine, anaesthesia and intensive care medicine in the UK and Ireland. Emergency Medicine Journal. TERN, Royal College of Emergency Medicine, London, UK Emergency Department, Bristol Royal Hospital for Children, Bristol, UK Department of Psychology, University of Bath, Bath, UK Statistical Consultant, Oxford, UK Department of Anaesthesi; 2021;38. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=150508893&lang=es&site=ehost-live.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Reignier J, Argaud L, Bruneel F, Courbon P, et al. Symptoms of mental health disorders in critical care physicians facing the second COVID-19 wave: a cross-sectional study. Chest. 2021;160(3):944–55.

Carmassi C, Pedrinelli V, Dell’oste V, Bertelloni CA, Cordone A, Bouanani S, et al. Work and social functioning in frontline healthcare workers during the covid-19 pandemic in Italy: role of acute post-traumatic stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms. Vol. 56, Rivista Di Psichiatria. [Carmassi, Claudia; Pedrinelli, Virginia; Dell’oste, Valerio; Bertelloni, Carlo Antonio; Cordone, Annalisa; Dell’osso, Liliana] Univ Pisa, Dept Clin & Expt Med, Pisa, Italy. [Dell’oste, Valerio] Univ Siena, Dept Biotechnol Chem & Pharm, Siena, Italy. [Bou; 2021.

Fiabane E, Gabanelli P, La Rovere MT, Tremoli E, Pistarini C, Gorini A. Psychological and work-related factors associated with emotional exhaustion among healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italian hospitals. Nursing Health Sci. 2021;23. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34333814.

Mattila E, Peltokoski J, Neva MH, Kaunonen M, Helminen M, Parkkila AK. COVID-19: anxiety among hospital staff and associated factors. Ann Med. 2021;53(1):237–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2020.1862905.

Simonetti V, Durante A, Ambrosca R, Arcadi P, Graziano G, Pucciarelli G, et al. Anxiety, sleep disorders and self-efficacy among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: a large cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(9–10):1360–71.

Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F, Demoule A, Kouatchet A, Reuter D, et al. Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Peritraumatic Dissociation in Critical Care Clinicians Managing Patients with COVID-19. A Cross-Sectional Study. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. Medical ICU, St. Louis University Hospital, Public Assistance Hospitals of Paris, Paris, France Medical ICU, Cochin University Hospital, University of Paris, Public Assistance Hospitals of Paris Center, Paris, France ICU, André Mignot Hospital, Le; 2020;202. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=147036481&lang=es&site=ehost-live.

Salopek-Žiha D, Hlavati M, Gvozdanovi Z, Gaši M, Placento H, Jaki H, et al. Differences in distress and coping with the covid-19 stressor in nurses and physicians. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(2):287–93.

Bettinsoli ML, Di Riso D, Napier JL, Moretti L, Bettinsoli P, Delmedico M, et al. Mental health conditions of italian healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 Disease Outbreak. Applied psychology. Health and well-being. 2020;12. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=33016564.

Fattori A, Cantu F, Comotti A, Tombola V, Colombo E, Nava C, et al. Hospital workers mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: methods of data collection and characteristics of study sample in a university hospital in Milan (Italy). BMC medical research methodology. 2021;21. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34376151.

Laurent A, Fournier A, Lheureux F, Louis G, Nseir S, Jacq G, et al. Mental health and stress among ICU healthcare professionals in France according to intensity of the COVID-19 epidemic. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-021-00880-y.

Gonzalez-Plaza E, Polo Velasco J, Rodriguez Berenguer S, Gimenez Penalba Y, Javierre Mateos A, Arranz Betegon A, et al. [Anxiety level of the healthcare workers of an obstetric unit during the COVID-19 pandemic]. Nivel de ansiedad de los profesionales de sala de partos durante la pandemia por COVID-19. 2022;49. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm5&NEWS=N&AN=34230736.

Heesakkers H, Zegers M, van Mol MMC, van den Boogaard M. The impact of the first COVID-19 surge on the mental well-being of ICU nurses: a nationwide survey study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2021;65:103034.

Hesselink G, Straten L, Gallee L, Brants A, Holkenborg J, Barten DG, et al. Holding the frontline: a cross-sectional survey of emergency department staff well-being and psychological distress in the course of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC health services research. 2021;21. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=34051760.

Abuye NO, Sánchez-Pérez I. Effectiveness of acupuncture and auriculotherapy to reduce the level of depression, anxiety and stress in emergency health personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Revista Internacional de Acupuntura. 2021;15(2):43–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acu.2021.04.001.

Azoulay E, de Waele J, Ferrer R, Staudinger T, Borkowska M, Povoa P, Iliopoulou K, Artigas A, Schaller SJ, Hari MS, Pellegrini M, Darmon M, Kesecioglu J, Cecconi M, ESICM. Symptoms of burnout in intensive care unit specialists facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00722-3.

Caillet A, Coste C, Sanchez R, Allaouchiche B. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on ICU Caregivers. Anaesthesia, critical care & pain medicine. 2020;39. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=33007463.

Carmassi C, Dell’Oste V, Bui E, Foghi C, Bertelloni CA, Atti AR, et al. The interplay between acute post-traumatic stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms among healthcare workers functioning during the COVID-19 emergency: a multicenter study comparing regions at increasing pandemic incidence. J Affect Disord. 2021. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medp&NEWS=N&AN=34728285.

Costa C, Teodoro M, Briguglio G, Vitale E, Giambo F, Indelicato G, et al. Sleep Quality and Mood State in Resident Physicians during COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34360316.

Diomidous M. Sleep and Motion Disorders of Physicians and Nurses Working in Hospitals Facing the Pandemic of COVID 19. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina). 2020;74. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med17&NEWS=N&AN=32801438.

Farì G, de Sire A, Giorgio V, Rizzo L, Bruni A, Bianchi FP, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in a cohort of Italian rehabilitation healthcare workers. J Med Virol. 2022;94(1):110–8.

Forner-Puntonet M, Fidel-Kinori SG, Beneria A, Delgado-Arroyo M, Perea-Ortueta M, Closa-Castells MH, de Estelrich-Costa MLN, Daigre C, Valverde-Collazo MF, Bassas-Bolibar N, Bosch R, Corrales M, Dip-Perez ME, Fernandez-Quiros J, Jacas C, Lara-Castillo B, Lugo-Marin J, Nieva G, Sorribes-Puertas M, Ramos-Quiroga JA. Clinical protocol for addressing mental healt needs of healthcare professionals during covid-19. Clinica y Salud. 2021;32(3):119–28. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2021a13.

Gago-Valiente FJ, Mendoza-Sierra MI, Moreno-Sánchez E, Arbinaga F, Segura-Camacho A. Emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and mental health in nurses from huelva: a cross-cutting study during the sars-cov-2 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7860.

Ilias I, Mantziou V, Vamvakas E, Kampisiouli E, Theodorakopoulou M, Vrettou C, et al. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Burnout in Healthcare Professionals During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: a Cross-Sectional Study. J critical care medicine (Universitatea de Medicina si Farmacie din Targu-Mures). 2021;7. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm&NEWS=N&AN=34722899.

Kapetanos K, Mazeri S, Constantinou D, Vavlitou A, Karaiskakis M, Kourouzidou D, et al. Exploring the factors associated with the mental health of frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Cyprus. PLoS One. 2021;16(10 October):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258475.

Laukkala T, Suvisaari J, Rosenstrom T, Pukkala E, Junttila K, Haravuori H, et al. COVID-19 Pandemic and Helsinki University Hospital Personnel Psychological Well-Being: Six-Month Follow-Up Results. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=33806283.

Leira-Sanmartín M, Madoz-Gúrpide A, Ochoa-Mangado E, Ibáñez Á. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and related variables: A cross-sectional study in a sample of workers in a spanish tertiary hospital. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7).https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073608.

Magnavita N, Soave PM, Antonelli M. Prolonged Stress Causes Depression in Frontline Workers Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic-A Repeated Cross-Sectional Study in a COVID-19 Hub-Hospital in Central Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34299767.

Magnavita N, Soave PM, Ricciardi W, Antonelli M. Occupational Stress and Mental Health among Anesthetists during the COVID-19 Pandemic/ Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med17&NEWS=N&AN=33171618.

Malinowska-Lipien I, Wadas T, Sulkowska J, Suder M, Gabrys T, Kozka M, et al. Emotional Control among Nurses against Work Conditions and the Support Received during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. [Malinowska-Lipien, Iwona; Suder, Magdalena; Gabrys, Teresa; Kozka, Maria; Gniadek, Agnieszka; Brzostek, Tomasz] Jagiellonian Univ Med Coll, Fac Hlth Sci, Inst Nursing & Midwifery, PL-31501 Krakow, Poland. [Malinowska-Lipien, Iwona; Wadas, Tadeusz] Malopo; 2021;18.

Moreno-Jiménez JE, Blanco-Donoso LM, Chico-Fernández M, Belda Hofheinz S, Moreno-Jiménez B, Garrosa E. The Job Demands and Resources Related to COVID-19 in predicting emotional exhaustion and secondary traumatic stress among health professionals in Spain. Front Psychol. 2021;12(March):1–12.

Moreno-Mulet C, Sanso N, Carrero-Planells A, Lopez-Deflory C, Galiana L, Garcia-Pazo P, et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on ICU Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed Methods Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34501832.

Nijland JWHM, Veling W, Lestestuiver BP, Van Driel CMG. Virtual Reality Relaxation for Reducing Perceived Stress of Intensive Care Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psycholo. 2021;12. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm&NEWS=N&AN=34659021.

Penacoba C, Velasco L, Catala P, Gil-Almagro F, Garcia-Hedrera FJ, Carmona-Monge FJ. Resilience and anxiety among intensive care unit professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing in critical care. 2021. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medp&NEWS=N&AN=34318963.

Schmid B, Schulz SM, Schuler M, Gopfert D, Hein G, Heuschmann P, et al. Impaired psychological well-being of healthcare workers in a German department of anesthesiology is independent of immediate SARS-CoV-2 exposure - a longitudinal observational study. German Med Sci : GMS e-journal. 2021;19. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34539301.

Singh L, Kanstrup M, Depa K, Falk AC, Lindstrom V, Dahl O, et al. Digitalizing a Brief Intervention to Reduce Intrusive Memories of Psychological Trauma for Health Care Staff Working During COVID-19: Exploratory Pilot Study With Nurses. JMIR formative research. 2021;5. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=pmnm5&NEWS=N&AN=33886490.

Sangrà PS, Ribeiro TC, Esteban-Sepúlveda S, Pagès EG, Barbeito BL, Llobet JA, et al. Mental health assessment of Spanish frontline healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Med Clin (Barc). 2021; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025775321007090.

Wesemann U, Vogel J, Willmund GD, Kupusovic J, Pesch E, Hadjamu N, et al. Proximity to COVID-19 on Mental Health Symptoms among Hospital Medical Staff. Psychiatria Danubina. 2021;33. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=34672286.

Vanni G, Materazzo M, Santori F, Pellicciaro M, Costesta M, Orsaria P, et al. The Effect of Coronavirus (COVID-19) on breast cancer teamwork: a multicentric survey. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2020;34. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med17&NEWS=N&AN=32503830.

Mortier P, Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Serra C, Molina JD, Lopez-Fresnena N, et al. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Depression and anxiety. 2021;38. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=33393724.

Van Steenkiste E, Schoofs J, Gilis S, Messiaen P. Mental health impact of COVID-19 in frontline healthcare workers in a Belgian Tertiary care hospital: a prospective longitudinal study. Acta clinica Belgica. 2021. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medp&NEWS=N&AN=33779529.

Morawa E, Schug C, Geiser F, Beschoner P, Jerg-Bretzke L, Albus C, et al. Psychosocial burden and working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: The VOICE survey among 3678 health care workers in hospitals. J Psychosomatic Res. 2021;144. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med18&NEWS=N&AN=33743398.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Reignier J, Argaud L, Bruneel F, Courbon P, et al. Symptoms of Mental Health Disorders in Critical Care Physicians Facing the Second COVID-19 Wave: A Cross-Sectional Study. CHEST. Medical Intensive Care Unit, AP-HP, Saint Louis University Hospital, Paris, France Medical Intensive Care Unit, University Hospital Center, Nantes, France Medical Intensive Care Department, Edouard Herriot Hospital, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon, ; 2021;160. Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=152061273&lang=es&site=ehost-live.

Sobregrau Sangra P, Aguilo Mir S, Castro Ribeiro T, Esteban-Sepulveda S, Garcia Pages E, Lopez Barbeito B, et al. Mental health assessment of Spanish healthcare workers during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. A cross-sectional study. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2021;112. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medp&NEWS=N&AN=34678607.

López-Atanes M, Recio-Barbero M, Sáenz-Herrero M. Are women still “the other”? Gendered mental health interventions for health care workers in Spain during COVID-19. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S243–4.

Hammarström A, Annandale E. A conceptual muddle: an empirical analysis of the use of ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ in ‘gender-specific medicine’ journals. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0034193.

Hammarström A, Johansson K, Annandale E, Ahlgren C, Aléx L, Christianson M, et al. Central gender theoretical concepts in health research: the state of the art. J Epidemiol Community Health (1978). 2014;68(2):185–90.

Clayton JA, Collins FS. Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature. 2014;509(7500):282–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/509282a.

Liszewski W, Peebles JK, Yeung H, Arron S. Persons of nonbinary gender — awareness, visibility, and health disparities. New England J Med. 2018;379(25):2391–3. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1812005.

Dimant OE, Cook TE, Greene RE, Radix AE. Experiences of transgender and gender nonbinary medical students and physicians. Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):209–16. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0021.

Westafer LM, Freiermuth CE, Lall MD, Muder SJ, Ragone EL, Jarman AF. Experiences of transgender and gender expansive physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2219791–e2219791. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.19791.

Phillips SP, Hamberg K. Doubly blind: a systematic review of gender in randomised controlled trials. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1):29597. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.29597.

Eurostat. Majority of health jobs held by women. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20210308-1#:~:text=Spotlight on women at the,90%25 in Estonia and Latvia.

Rich-Edwards JW, Kaiser UB, Chen GL, Manson JAE, Goldstein JM. Sex and gender differences research design for basic, clinical, and population studies: essentials for investigators. Endocr Rev. 2018;39(4):424–39.

Rich-Edwards JW, Kaiser UB, Chen GL, Manson JE, Goldstein JM. Sex and gender differences research design for basic, clinical, and population studies: essentials for investigators. Endocr Rev. 2018;39(4):424–39. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2017-00246.

Avery E, Clark J. Sex-related reporting in randomised controlled trials in medical journals. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):2839–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32393-5.

Brady E, Nielsen MW, Andersen JP, Oertelt-Prigione S. Lack of consideration of sex and gender in COVID-19 clinical studies. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4015. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24265-8.

Carrillo MJ, Martín U, Bacigalupe A. Gender inequalities in publications about COVID-19 in Spain: authorship and sex-disaggregated data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2025.

Shapiro JR, Klein SL, Morgan R. Stop ‘controlling’ for sex and gender in global health research. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(4):e005714. Available from: http://gh.bmj.com/content/6/4/e005714.abstract.

Bolte G, Jacke K, Groth K, Kraus U, Dandolo L, Fiedel L, et al. Integrating sex/gender into environmental health research: development of a conceptual framework. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12118.

Nadal KL. Gender Stereotypes. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Psychology and Gender. 2017;(September 2017):1–24.

Ellemers N. Gender Stereotypes. Annu Rev Psychol. 2018;69(1):275–98. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719.

Staiger T, Stiawa M, Mueller-Stierlin AS, Kilian R, Beschoner P, Gündel H, et al. Masculinity and help-seeking among men with depression: a qualitative study. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11(November):1–9.

Guille C, Frank E, Zhao Z, Kalmbach DA, Nietert PJ, Mata DA, et al. Work-family conflict and the sex difference in depression among training physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1766–72.

Scholcoff C, Farkas A, Machen JL, Kay C, Nickoloff S, Fletcher KE, et al. Sexual harassment of female providers by patients: a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(10):2963–8.

Jenner S, Djermester P, Prügl J, Kurmeyer C, Oertelt-Prigione S. Prevalence of sexual harassment in academic medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):108–11. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4859.

Lighthall NR, Mather M, Gorlick MA. Acute stress increases sex differences in risk seeking in the Balloon Analogue Risk Task. PLoS One. 2009;4(7):e6002.

Apsley HB, Vest N, Knapp KS, Santos-Lozada A, Gray J, Hard G, et al. Non-engagement in substance use treatment among women with an unmet need for treatment: A latent class analysis on multidimensional barriers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023;242:109715. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0376871622004525.

Sullivan L, Camic PM, Brown JSL. Masculinity, alexithymia, and fear of intimacy as predictors of UK men’s attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20(1):194–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12089.

Gonzalez JM, Alegría M, Prihoda TJ, Copeland LA, Zeber JE. How the relationship of attitudes toward mental health treatment and service use differs by age, gender, ethnicity/race and education. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46(1):45–57.

Government of Canada CI of HR. How to integrate sex and gender into research - CIHR. 2018. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50836.html.

Acknowledgements

The review team acknowledges the Cruces University Hospital and the Leibniz Institute for prevention research, the institutions under which this review was conducted, for their support and commitment to gender equality.

Patient consent for publication

We used secondary data, for this reason patient consent was not needed.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML conceived the study. ML, MS and TB designed the study. ML, TB, EF and MS contributed to the methods. ML, AU, ML and NZ extracted the data. ML, LE, TB and IS contributed to the writing of the manuscript. RS and TB provided supervision. All authors contributed to the data interpretation and review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We used secondary data, for this reason ethics approval was not needed.

Consent for publication

All authors revised and approved the submission of this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

López-Atanes, M., Sáenz-Herrero, M., Zach, N. et al. Gender sensitivity of the COVID-19 mental health research in Europe: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health 23, 207 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02286-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02286-1